Georg Berg/Alamy

Three centuries after it was rediscovered, Royston Cave remains one of Britain’s most mysterious places.

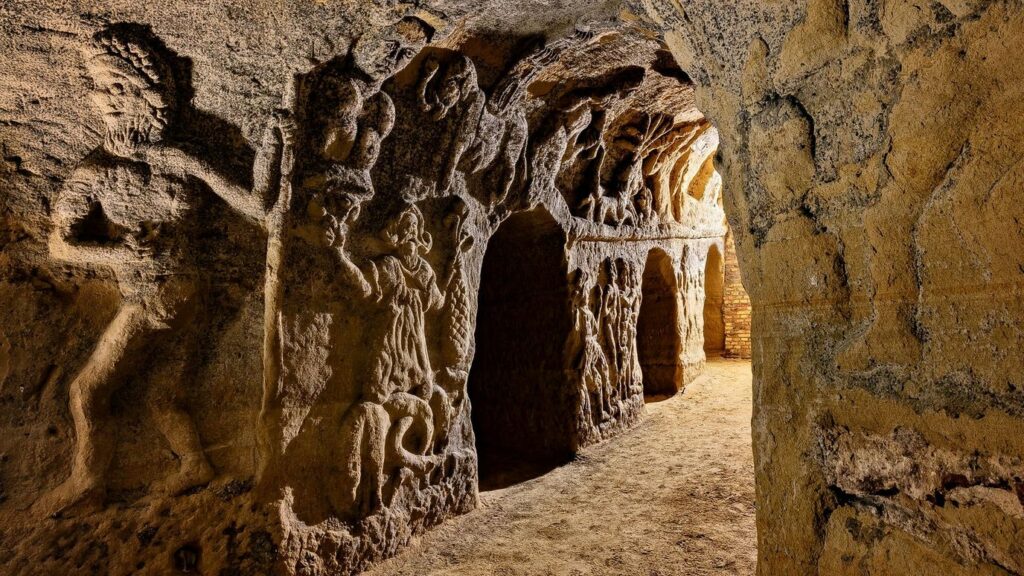

n a hole in the ground beneath the Hertfordshire market town of Royston, dimly illuminated by flickering light, I was looking at a gallery of crudely carved figures, blank-faced and bearing instruments of torture. Cave manager Nicky Paton pointed them out to me one by one. “There’s Saint Catherine, with her breaking wheel. She was only 18 when she was martyred,” Paton said, cheerfully. “And there’s Saint Lawrence. He was burnt to death on a griddle.”

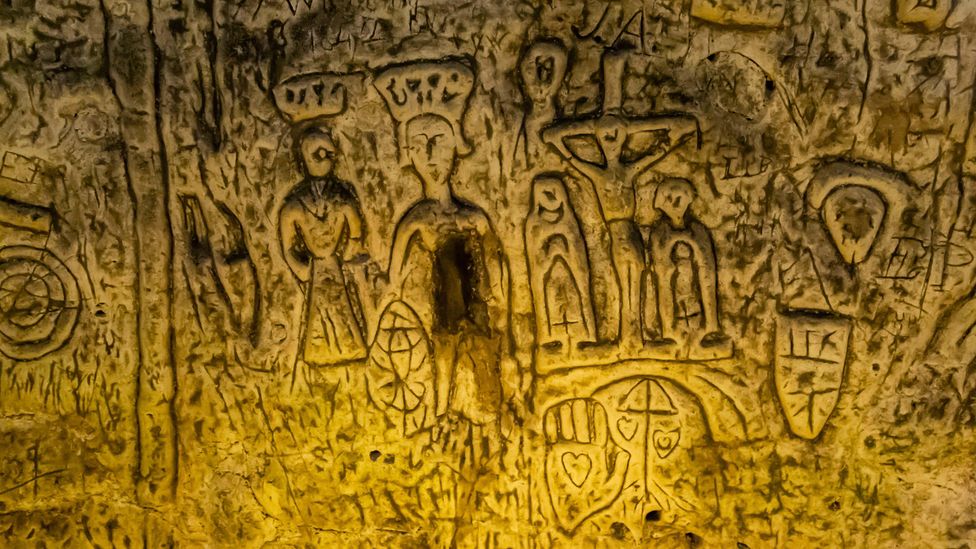

Amid the grisly Christian scenes were Pagan images: a large carving of a horse, and a fertility symbol known as a sheela na gig, depicting a woman with exaggerated sexual organs. Another portrayed a person holding a skull in their right hand and a candle in their left, theorised to represent an initiation ceremony – a tantalising clue as to the cave’s possible purpose. Adding to the carvings’ creepiness was their rudimentary, almost childlike, execution.

Imagine the surprise, then, of the people who rediscovered Royston Cave, quite by accident, in the summer of 1742. A workman, digging foundations for a new bench in the town’s butter market, struck a buried millstone and found that it was hiding the entrance to a deep shaft in the earth. This being an age before the dawn of health and safety directives, a passing small boy was promptly handed a candle and sent down on a rope to investigate, while the townsfolk of Royston chattered excitedly above about the prospect of buried treasure.

What was discovered was less lucrative but far more mysterious: a broken cup and some jewellery, a human skull and bones, and walls engraved from top to bottom with strange expressionless figures. Three centuries later, Royston Cave remains one of Britain’s most mysterious places, with ever more theories as to its purpose leading no closer to an answer.

The cave was rediscovered in 1742 by a workman digging in the town’s butter market (Credit: Chris Howes/Alamy)

“What makes the cave so intriguing to visitors and historians is that it’s still an enigma; still a mystery as to who made it, or when or why,” said Paton. “That’s mainly because there is no documentation about its existence prior to that accidental discovery. No books, no drawings, no diaries – nothing to suggest it was even here.”

What makes the cave so intriguing to visitors and historians is that it’s still an enigma; still a mystery as to who made it, or when or why

There are, however, plenty of theories. Those of an esoteric disposition have claimed that the cave lies at the intersection of two ley lines – ancient pathways theorised to connect places of spiritual power – one of which, the so-called Michael Line, also runs through Stonehenge and Avebury.

More easily verifiable is the fact that the cave lies directly beneath the intersection of two highly significant ancient roads: the Icknield Way, a historical trackway that runs along southern England’s chalk escarpment from Norfolk to Wiltshire; and Ermine Street, a Roman road that originally ran from London to York. A large footstone is now all that remains of a cross that once stood at the junction of these two roads, named for Lady Roisia, a local noblewoman after whom Royston is thought to have been named.

The cave walls are engraved from top to bottom with strange expressionless figures (Credit: Daniel Stables)

The antiquarian William Stukeley, who visited Royston a couple of months after the cave’s rediscovery in 1742 and wrote an early study as to its purpose, noted that such crosses were common at major junctions, and served two purposes in an age of high religiosity and low literacy: “To put people in mind of saying their prayers; and of directing them in the road they wanted to go.” Holy people would, he wrote, build “cells and grottos in rocks and caverns, and by highway sides”, directing travellers and praying for them. A prominent carving in the cave depicting Saint Christopher, patron saint of travellers, lends credence to the theory that the cave served as this kind of hermitage.

However, the theory that has ensnared the public imagination more than any other is that Royston Cave was an underground hiding place for the Knights Templar, that enigmatic order of warrior monks who achieved vast wealth and influence across Europe before being violently suppressed in 1307.

The Templars founded the nearby town of Baldock in the 1140s and are documented to have traded weekly at Royston’s butter market between 1149 and 1254. Local historian Sylvia Beamon believes the cave was a pre-existing structure that was used by the Templars to store perishable food, for their many daily prayers and to stay overnight on market days, after they had several documented disputes with the Prior of Royston and so were no longer welcome in Royston Priory.

“A Templar chapel probably became more of a necessity than anything else,” she wrote in her 1992 book, Royston Cave: Used by Saints or Sinners?, “giving a haven overnight for the Templar marketeers, and… a warehouse for market goods.” She interprets the circular design of the cave as a reference to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and suggested that the carvings bear hallmarks of Templar art, such as their depiction of heart symbols and the biblical King David.

The provenance of the carvings, however, is impossible to prove. While it’s thought the cave would once have been brightly painted, very little pigment remains, and that which does is too contaminated to be carbon dated. There is no other organic material in the cave that can be dated – the human remains, discovered in an age before modern conservation practices, have long been lost. The most reliable way to date the carvings is by a stylistic examination, which was carried out in 2012 by the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds.

The cave lies directly beneath the intersection of two highly significant ancient roads

The analysis found that the short male costumes and the headdresses and hairstyles of the women both point to a time between 1360-90, and the Saint Christopher carving was dated to the same era. The report concluded that it was unlikely that any of the carvings were executed before about 1350 – a century after the Templars were active in Royston, and decades after their widespread suppression. What’s more, the carvings feature Christian iconography, lacking the symbolism typically associated with the Templars – depictions of the Holy Sepulchre and Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, for example, or of two knights riding one horse.

Although the Knights Templar were known for building round churches, the circular shape of the cave does not necessitate a Templar link either – the greatest proliferation of round churches is in Scandinavia, where no Templars ever set foot. Nor is the presence of Pagan symbols such as the sheela na gig particularly mysterious; the same image appears in medieval churches across Britain and Europe.

Why, then, the supposed Templar connection? Perhaps the things that make for a good story now also made for a good story in 1742. “The risk here is people have been wanting to tell stories since day one: ‘Come and see the Templar cave!’,” said Tobit Curteis, the conservator of the cave. “Just because someone made up a story 300 years ago, it doesn’t mean it was any more true back then than it would be now.”

Despite a lack of proof, many people believe that Royston Cave was an underground hiding place for the Knights Templar (Credit: Daniel Stables)

Professor Helen Nicholson, medieval historian and author of several books on the Templars, agrees. “People in England have been fascinated by the Templars ever since they were abolished in the 14th Century,” she said. The trials against the Templars included accusations that they conducted shady ceremonies in secret underground hiding places. “In effect, they are Gothic horror stories; they were probably dreamed up because people who had worked with the Templars were under severe pressure from papal inquisitors to say something to support the accusations,” Nicholson added. “In any case, these stories are probably the reason why the carvings in the cave at Royston [were] ascribed to the Templars. In real life, the Templars were not a subterranean order.”

We’ve lost 99% of the other artwork from that period, so the cave really is incredibly special. Just maybe not for the reasons that some people think

The real wonder of the cave, Curteis says, is its survival and rediscovery. “We’ve lost 99% of the other artwork from that period, so the cave really is incredibly special. Just maybe not for the reasons that some people think.”

Which is not to say that Royston Cave is not a great mystery. Somebody, probably in the mid-late 1300s, made those carvings, of which the most striking – the figure holding a skull in one hand and a candle in the other – remains unexplained. It might be easy to put it down to a bit of myth-making graffiti, added soon after the cave’s discovery in order to attract tourists, were it not for the way in which it chimes with the human skull, ceremonial pottery and jewellery also found in the site.

In an age where most mysteries get solved, Royston Cave continues to provide more questions than answers. That includes the most tantalising question of all: what else lies beneath our feet, waiting to be found?

Hidden Britain is a BBC Travel series that uncovers the most wonderful and curious of what Britain has to offer, by exploring quirky customs, feasting on unusual foods and unearthing mysteries from the past and present.