No 2022 show was more controversial than Ryan Murphy’s Netflix show about the serial killer – but there were other real-life dramas that raised ethical concerns too, writes Hugh Montgomery.

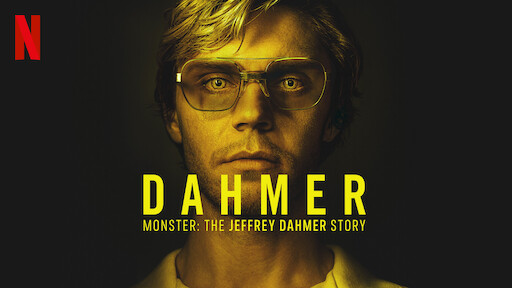

Few recent cultural works have shown up the divide between critics and audiences quite like this year’s awkwardly-titled Netflix series Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. The drama about notorious US serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, who murdered 17 young men and boys between 1978 and 1991, was released mid-week in September on the streaming service, with little pre-publicity and no previews made available for press – a common indication that the show or film in question isn’t much good. And duly, the media verdicts that did come in were mostly pretty harsh.

By contrast, though, viewing figures proved astronomical: according to Netflix’s self-declared ratings, it was watched for 196.2 million hours in its first week of release, at the time giving it the best opening week for a new show on the streaming platform ever, while within 60 days it reached 1 billion hours viewed, placing it in the rare echelons of other globe-conquering cultural phenomena Stranger Things and Squid Game. Whether all those eyeballs on it were favourable – though a 83% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes would suggest most of them were – undeniably people could not stop watching its incredibly grim story play out. And matching the size of its cultural footprint has been the level of debate that it has stirred.

The root of that contentiousness is perhaps best illustrated by a comparison with another true-crime drama, featuring a number of narrative parallels, which premiered at the very beginning of the year. The BBC miniseries Four Lives also focused on the horrific case of a serial killer who murdered young gay men, Stephen Port, as well as the resulting police failings in dealing with the victims’ cases that were alleged by some to be driven by institutional prejudice (homophobia in the Port case and both homophobia and racism in the Dahmer one). Except the whole style and tone of Four Lives was sombre and restrained: when Port appeared, he was a pointedly blank, banal supporting character, with no backstory sketched in, while from the title onwards, the show emphasised that this was the story of his four victims only – or rather the victims’ families, for the most part, who consented to and/or cooperated with the show and were depicted fighting for justice for their loved ones.

Where Four Lives was sober, though, Dahmer was unabashedly lurid. In its first half in particular, it centred firmly on the killer, played by Evan Peters, taking us inside his world and flashing back to his early development and broken family life while, in the present timeline, featuring graphic, extended sequences of him entrapping his targets within his grisly apartment. Creator Ryan Murphy made his name in part with the homage-filled horror of his anthology series American Horror Story, and here he leans once more into the grammar of horror – the bolts going across the door, the ominous pan across the drill on the kitchen workspace – in ratcheting up the sense of dread. As reviewer Jack King wrote for GQ “it feels as though Murphy is aping the likes of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes, Peters’ performance not so distant from a socially-stunted Hannibal Lecter”.

What’s more, it was made without the consent of any of the victims’ families – and since its release, a number of them have publicly expressed their upset at the show’s existence. That has compounded the feeling among many critics that the show isn’t simply bad, it is indecent. The Guardian asked “Is Ryan Murphy’s Jeffrey Dahmer show the most exploitative TV of 2022?” while an article by Anna Leszkiewicz in the New Statesman, baldly entitled Abolish True Crime, went as far as to suggest that the series proves the genre is “morally indefensible”.

The key questions it raises

Without doubt, the conversation around it lends itself to a wider discussion about the whole nature of what we watch, or should watch, when it comes to true-crime drama and beyond. First of all, it raises the question of focus: is giving a serial killer a narrative platform in itself an act of mythologising and glorification? That has been an increasing feeling within the cultural ether, as a range of works, from books to documentary and docudrama series and films, have made a concerted effort to instead refocus narratives away from notorious murderers and onto their targets. By the same token, in citing evidence for the corruptive consequences of serial killer-centred narratives, some have pointed to the Dahmer-related Tik Toks that have sprung up in the show’s wake, in which users have apparently expressed sorrow or sympathy for Dahmer or created “romantic” edits of scenes with him.

So should serial killers become characters non grata in – or at least be pushed to the background of – film and TV drama? Jarryd Bartle, a criminology and justice studies lecturer at Melbourne’s RMIT University, who has written about true crime and the Dahmer show itself, believes there can be no hard and fast rule on this matter. In fact, he is more sympathetic to the show than many reviewers, pointing out that it does have more of a focus on the victims than many other true-crime dramas, and many other film and TV treatments of the Jeffrey Dahmer story: the second half of the series does indeed refocus away from Dahmer and towards the victims, and their families, with a single victim, deaf, aspiring model Tony Hughes, becoming the focus of one particular episode.

But Bartle also says that, while he believes there is benefit in making such dramas more victims-centred, he thinks “it is sometimes difficult to tell these stories without getting into the killer themselves and their motivations”. Plus, he adds, “we know from research, in terms of why people watch true crime, that one of the main interests people have is trying to understand the psychology of why people kill”. And as for those Tik Toks? “I’m not aware of any research indicating that there are greater rates of this kind of problematic fascination with serial killers these days than there had been in the past,” he says. “We’ve had people be fans of killers in problematic ways for a very long time.” Indeed, the Dahmer series itself deals with this, showing people back around the time of his arrest writing him “fan mail” in prison.

There there is the question of consent: should true crime dramas only go ahead with the permission of those closely connected to the crimes, given the significant potential for retraumatising? Some would say it should be an absolute line in the sand: as Vox culture reporter Aja Romano wrote: “Make your true crime dramas if you must but make them with the assistance of and respect for the victims. Model your true crime dramas after Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us [the Netflix drama about the Central Park Five] made with the full support of its subjects, rather than at their expense”.

What I’ve found is that actually there are a lot of people that haven’t heard that story before that have now been exposed to it – and I do think there is some benefit to that – Jarryd Bartle

However Bartle is again less clear-cut on the rights and wrongs around this issue, given that, as he sees it, the “ethical dilemmas” around platforming a horrific case via a TV drama are not much different from those in crime reporting generally. “[Whatever the medium] there is often a resistance by family members of victims to see something turned into any kind of spectacle that relates to their loved ones and that’s completely natural.” On top of that, he says, the public interest in telling and retelling some stories has to be taken into account. In the case of Netflix’s Dahmer series, he does believe it meets that public interest bar, given the way it suggests how systemic homophobia and racism underlay the tragedy – and also, that while the story may have told many times over, making it into a fictional drama on a mass market streaming platform necessarily will expose it to different audiences. That’s something he has felt first hand from speaking to people since the series’ release: “If you’d told me two years ago they’re going to make another story about Jeffrey Dahmer, I probably would have been a bit more dismissive in saying ‘we’ve had this story told hundreds of times before in different medium’. But what I’ve found is that actually there are a lot of people that haven’t heard that story before that have now been exposed to it – and I do think there is some benefit to that.”

Murphy himself is keen to emphasise this public interest aspect: having remained quiet around the September release, he has more recently been speaking about the show, and justifying its making. “We weren’t so much interested in Jeffrey Dahmer, the person, but what made him the monster that he became,” he has said, adding that “It’s really about white privilege. It’s about systemic racism. It’s about homophobia”. However it’s a framing of the show that, whatever one’s opinions about its relative virtues, or lack of them, cannot help but seem disingenuous, given the show’s evident dedication to centring “Jeffrey Dahmer, the person”, from those aforementioned horror movie sequences to the marketing, which has focused tightly on Evan Peters’ sinister, bespectacled visage. “His portrait is coloured with a warm lustre, set between metallic gold panels,” wrote Leszkiewicz in the New Statesman of seeing Peters’ Dahmer on a LED billboard in central London. “Dahmer has, quite literally, been exalted: raised high over the city in a gilded frame like a god.”

The troubles with the real-life drama explosion

If Dahmer has been particularly controversial, then it’s far from the only show this year about real people to have got into hot water. Ripped-from-the-headlines dramas seem to be becoming ever more prevalent, and so it’s no wonder that, in tandem with that, the whole issue of fictionalising real people on screen has become increasingly contentious, both when it comes to their representation and their approval. Some other shows that have stirred debate on this front in 2022 include: Pam and Tommy, Hulu’s miniseries about Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee’s stolen “sex tape”, a story about a woman’s most personal experiences being seen by the world without her consent which ironically did not gain Anderson’s consent to be made; and The Crown, with a particular fury being whipped up around the latest series and its bending of the facts, perhaps because, as it gets closer to the present day, memories become sharper. Then there was Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal, the bizarre HBO show in which comedian Fielder purported to help people rehearse key moments in their life, and blurred the boundaries between reality and fiction in a way that some felt was inherently problematic (although arguably, too, that was the point).

What’s more, it’s a conversation that has crossed over into the legal realm, with action either being taken or threatened by those portrayed or referenced in high-profile shows about their depiction. In September, Netflix settled a lawsuit with Georgian chess master Nona Gaprindashvili over an inaccurate reference to her in their hit 2020 miniseries The Queen’s Gambit. Meanwhile in August it was revealed Rachel DeLoache Williams, the former friend of “fake heiress” Anna Sorokin, was suing Netflix for defamation and false light invasion of privacy for her depiction in this year’s Inventing Anna. In June, Michael Peterson suggested he was planning to consult lawyers about the making of the HBO drama The Staircase, exploring the notorious true-crime case of his wife’s death, which he described as containing “egregious fabrications”. And in Dahmer’s case, a tabloid newspaper report in October suggested Jeffrey Dahmer’s father Lionel was seeking legal advice against Netflix for its two Dahmer shows, Murphy’s drama and the documentary series Conversations with a Killer: The Jeffrey Dahmer Tapes, according to Lionel’s assistant – though it’s not clear in this case what his basis for a legal challenge would be.

There will be a pressure on TV makers to be more careful in their message – are they producing facts or are they producing fiction? – and make sure the viewer knows which is which – Helena Shipman

“I’d certainly say that we’ve noticed an upturn in this kind of inquiry,” says Helena Shipman, a specialist in defamation at solicitors Carter-Ruck about cases involving the depiction of people in TV dramas. And while there may not have been any major victories on this front yet, Shipman says the law in this area hasn’t really been tested – “so I don’t think we can safely say that Netflix [and others] have got nothing to worry about. In fact, quite the opposite”. Undoubtedly, she thinks, with the increasing amounts of based-on-a-true-story dramas being made, “there will be a pressure [on TV makers] to be more careful and that is careful in their message – are they producing facts or are they producing fiction? – and it’s incumbent on them to be much more careful to make sure the viewer knows which is which.” Saying that, though, a simple disclaimer – of the kind seen before episodes of Inventing Anna (“This whole story is completely true. Except for all the parts that are totally made up”) and in the trailer for the most recent series of The Crown (which described it as “inspired by real events” and a “fictional dramatisation”) – does not get TV-makers off the hook. “That’s neither here nor there,” says Simpson. “Unless it’s made absolutely clear which parts are fiction and which parts are fact, then the producer is shifting the onus of working that out onto the viewer – but actually the legal responsibility lies with the producer and the publisher.”

But legal ramifications are one thing, and morality quite another. So are we drifting into dangerous territory with the explosion of these real-life dramas? And ethically, are the makers of them going too far – or rather, not far enough? It definitely feels like we’ve reached a point where conversations – about representation, consent, and the sheer necessity of recreating certain traumatic events as dramatic entertainment – are coming to a head.

Yet at the same time, the ratings for Dahmer speak for themselves. Perhaps, as Bartle suggests, there’s an instinctive morbid curiosity driving people to watch such a show that is timeless. “It has been a well-documented feature of humans throughout history,” he says. “And I do think some of the criticisms that I’ve seen of the Dahmer series are very quick to view that as necessarily a corruptive or bad impulse, but I view it as a natural [one]… I would be more disturbed if there was some kind of moral regime to say ‘people don’t need to know about these things, people don’t need to hear about graphic crimes’. That to me is a more counterproductive social impulse.”

Equally, a viewer may condemn a piece of work as unethical, but that may not necessarily stop them watching it all the same – such is the fickle nature of human behaviour. Indeed, the almighty backlash against Dahmer hasn’t stopped a whole “Monster” anthology series focusing on “other monstrous figures who have impacted society” now being commissioned – something that has made its critics get more queasy, with the suggested implication, via Netflix’s talk of a Monster “universe”, that real-life “monstrous figures” are as franchisable as superheroes or space operas. Bartle himself will be reserving judgment, saying “each new entry needs to be judged on its own merits”, though he does wonder “if they’re going to learn from some of the backlash about victims’ families this time around and [factor] that in for future series”. Certainly, there will be a lot of people watching intently.