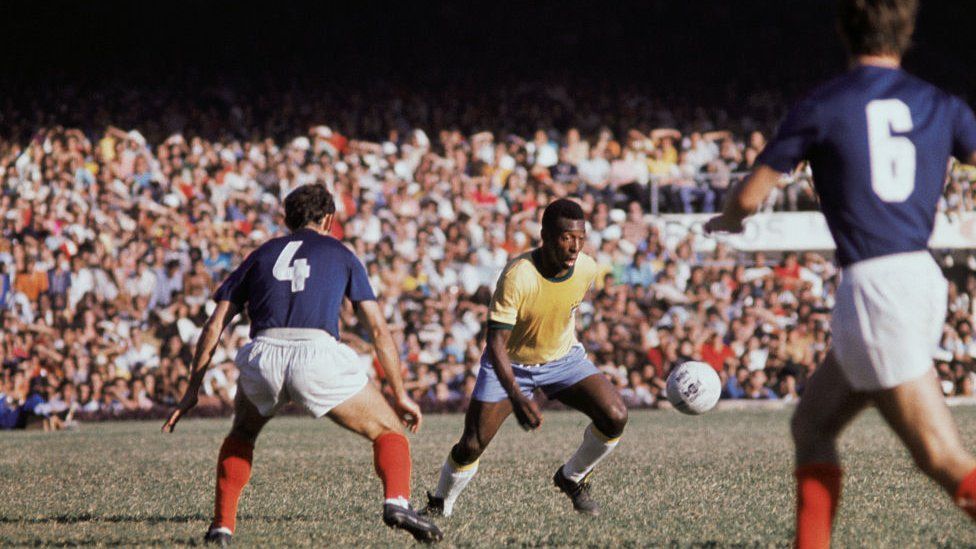

GETTY IMAGES, “O Rei”, Pelé, playing for the Brazilian national team at the Maracanã stadium in Rio de Janeiro

Pelé, o Rei, has died.

Brazil and the world are grieving, and many of us mourn an idol we never saw on the pitch.

Being 23 years old, I was not around during the start, middle, or even the end of his glowing football career. But that does not matter. Pelé was and always will be a household name.

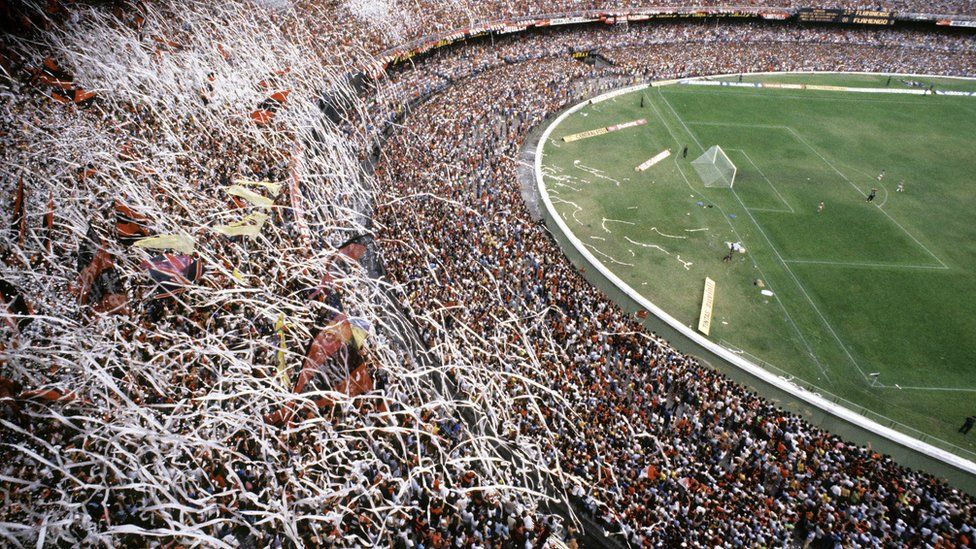

Growing up in Rio de Janeiro, a city of exuberance and vibrancy, football played a crucial role in our life.

Maracanã, where Pelé scored his thousandth goal, was emblematic of my day-to-day routine until I moved to the UK, aged 11.

We were always nearby. The buzz and frenzy during match days could be felt across the city. Traffic would be slower, restaurants busier, and the streets much louder.

Following the news of king Pelé’s death last night, as I was writing for the BBC’s tributes live page, my family group chat kept buzzing.

Four generations, all devastated in equal measure by the death of an idol. Words, emojis and GIFs expressed our shock – we are Brazilian, after all, and emotions tend to run high.

But what stuck with me was a comment from my aunt. She highlighted that Brazilian media, while discussing Pelé’s life, used the phrase: “Our king is black.”

GETTY IMAGES, Thousands of football fans from across Brazil flock to Rio de Janeiro to watch big matches at Maracanã

His stardom is unquestionable – and his influence worldwide says much more about him than his ethnicity and background.

But for Brazil’s black community, hearing those words matter. A lot. And they signify a paradigm shift we have been going through for decades – one in which Pelé played a crucial role in.

Because Pelé rose to the status of a national treasure in a country with a deep history of slavery, and a legacy of division.

He regularly faced monkey chants on the pitch and had several racist nicknames. He once said that if he had stopped every game after a monkey taunt, he would have had to stop them all.

He was key to carving out space and recognition for black people in Brazilian football, his biographer Angelica Basthi has said – but he was never directly involved in the fight against racism.

Speaking to my mum, she tells me that Pelé “signifies greatness and contradiction”.

Contradiction, because many Brazilians struggled with his resistance to speak out against racism.

Greatness, due to the path he forged for us, black Brazilians. Pelé rose to stardom despite Brazil’s deeply rooted racism.

“He allowed us, black Brazilians, to see one of our own being acclaimed by the masses, considered a King, an icon for the whole country,” my mum tells me.

“Pelé won his first World Cup only 70 years after slavery was abolished [in Brazil], in a country which continued, and continues, to treat black people as third-class citizens.

“He was an icon, who made us realise that it is possible to be a black man of international prominence.”

Brazil abolished slavery in 1888. It is not ancient history for us, and anti-black racism continues to be rife.

Pelé’s voice and gravitas could be heard in the commentary of big games long after the end of his career – particularly during World Cups.

“Even being quiet, he was able to contribute a lot towards Brazil’s image worldwide,” Edward Helal, my friend and a huge football fan, tells me.

Asked about the mood in Rio, Edward says most people are taking time to pay tributes and express their gratitude to the king of football.

Even now, during my annual visits back home, I dare not suggest having anything other than our world-renowned football commentary in the background on a Wednesday evening or Sunday afternoon.

I have Pelé to thank – and blame – for it.

Absolutely written subject material, appreciate it for entropy.